Eddie Rickenbacker set the tone for generations of pilots to come

Monday, May 22, 2017

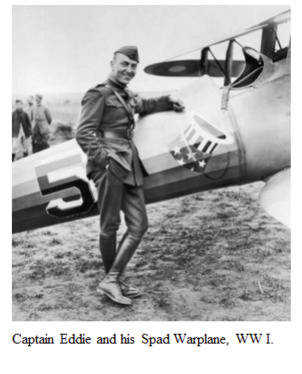

Eddie Rickenbacker with his “Hat-in-the-Ring” squadron insignia.

(Note: Perhaps the most important of the scientific innovations that were spawned by World War I was the development of the airplane. Just 11 years after the Wright Brothers proved to the world that powered flight was not only possible but even practical, most of the countries of the civilized world rushed to develop their own entry into the new air age. In doing so, they unleashed a most new, extremely effective killing machine that changed the nature of war forever.)

One of the most colorful characters to emerge from World War I, and certainly the most popular with the American public was Ace Pilot, Capt. Eddie Rickenbacker. This was probably because Rickenbacker was already a hero on the car racing circuit before he entered the Army, and also because aviation was a new phenomenon — one that had completely captured the public’s attention. Rickenbacker most fit the mold of a “Knight of the Air” of any of the American aviators. Indeed, he was a swashbuckler, a throwback to another age. His confidence and his swagger set the pattern for wartime pilots in World War II, and even the Space Age.

Edward Vernon Rickenbacker was born in 1890, the third of eight children of a small contractor in Columbus, Ohio. The family was always dreadfully poor, and young Rickenbacker worked at a series of part-time jobs from the time he was seven years old. When his father died, 12-year-old Eddie went to work full time to lend his support to his mother and the younger children. He gravitated to the automotive industry (then in its infancy), working in garages---anything to be near automobiles. At night he took courses in mechanical engineering from International Correspondence School, finishing in 1905. These courses prepared him sufficiently to land a job with the Frayer-Miller Air-cooled Car Co. — just one of many new auto companies that emerged in the early 1900s.

In 1909 Rickenbacker became branch sales manager of the Firestone Tire Co., traveling throughout the Midwest. In 1910 he began racing automobiles on small-town dirt tracks. He began racing in earnest in 1912 and raced for a number of sponsors. By the time war had broken out in Europe in 1914 he had formed his own racing team, the “Maxwell Special”, racing in cities throughout the US and England, which he continued until the US entered the war in 1917.

Rickenbacker had a stellar racing career. He raced three times in the Indianapolis 500, even then the country’s leading auto race. He set a speed record of 134 MPH in a Blitzen Benz.

He was one of the most successful racecar drives in the country, earning $40,000 per year ($905,000 in today’s dollars), an incredible sum for that time.

When the United States entered the war in 1917, Rickenbacker suggested to the Army that they recruit racing drivers, and turn them into flyers. The Army turned down Rickenbacker’s suggestion, but accepted his services---as a driver for the Army general staff, with the rank of Sergeant. This was acceptable to Rickenbacker. He just wanted to get overseas. He figured that once in France he would find a way to get to fly.

In France, Rickenbacker got a break, when he had a chance to fix the motorcar carrying Col. Billy Mitchell, the Chief of the Army’s Air Service. Even though at 27, Rickenbacker was considered old for flying, Mitchell arranged for Rickenbacker to enter pilot training, earning a commission, as 2nd Lt., while acting as Engineering Officer at Issoudun Aerodrome in France.

Even though Rickenbacker was determined to become a pilot, he did not take to flying automatically. His problem was airsickness. The first 15 flights he made he became terribly nauseated and each of these flight lessons came to an inglorious end as the instructor was forced to take over the controls. But Eddie was nothing if not determined, and he eventually overcame his airsickness. After that, he mastered the basic maneuvers of flying in a very short time.

In March 1918 he was assigned to the 94th Pursuit Squadron, which was to become famous as the 94th “Hat in the Ring” Squadron. With a few cast-off Nieuport planes (Later, replaced by newer, faster Spads), they moved up to the front. Before the war ended the 94th would record the most victories over enemy planes of any American Squadron.

In the first years of World War I, both the Germans and the French and British fought mainly trench warfare. For this type of fighting, observation balloons were important means for procuring information about enemy movements. As the war went on airplanes were used, first as photography planes, and then as weapons to attack, or to protect the observation balloons. Only in the latter months of the war did “dogfights”, planes attacking other planes, become widespread.

For 10 weeks Rickenbacker flew strafing missions and fruitless sorties before shooting down his first enemy plane. Then, in a period of only two months he recorded 26 enemy planes shot down — the most of any American airman — even though during much of this time he suffered from an attack of pneumonia and an ear infection.

Rickenbacker’s immediately earned the admiration of a grateful American public, and in 1930, 12 years after the war ended, the Army acknowledged his spectacular achievement by awarding him the Congressional Medal of Honor.

In the postwar 1920s Rickenbacker headed a new automobile company, carrying his name. The Rickenbacker car was well engineered, with much automotive advancement, including four-wheel brakes. It was far ahead of its time — too far as it turned out. Competitors convinced the public that four-wheel brakes were untested and dangerous. The company went bankrupt.

In 1927 Rickenbacker raised $700,000 in one month and bought the Indianapolis Motor Speedway. He knew its importance as a testing ground for automobile technology. It was he who constructed the 18-hole golf course in the infield of the 2 ½- mile track, as a source of needed extra income. He sold the track in 1947.

In 1925 Rickenbacker, with one of his Army buddies, bought the air arm of General Motors, Eastern Airlines, for $3.5 million---raising the money in just weeks, barely before John Hertz, of rental car fame, could exercise his option to buy the company.

Under Rickenbacker’s management, Eastern greatly expanded — using government airmail contracts and expanded air routes, across the US southern tier and into Mexico. Rickenbacker remained chairman of the board of a successful Eastern Airlines until Dec. 31, 1963.

As World War II approached, Rickenbacker took to the political stump, giving speeches across the country, promoting “America First,” and vehemently opposing our taking on Europe’s troubles. He had stayed in touch with World War I flyers, both Allied and German, and pointed out the advances that the Germans had made in Aviation (much more than had the Americans).

Nevertheless, when the US did enter the war, Rickenbacker volunteered his services to the country. Gen. “Hap” Arnold sent him to visit airbases throughout the Southeast US to bolster the morale of pilots. On one of these trips, he was in an airline crash. It took him three months to recuperate from his injuries.

In September 1942 Secretary of War Stimson asked Eddie to tour bases in England to inspect the facilities and seek out evidence of espionage. Upon his return, he was asked to proceed immediately on a similar tour of bases in the Pacific Theater.

On this tour Rickenbacker, his aide, Col Hans Adamson, and their B-17 crew visited Hawaii, then set out for Port Moresby, New Guinea. Somehow, hampered by inadequate navigational equipment and a faulty weather report, they overshot their destination. They were forced to ditch their plane in the Pacific. They were lost at sea for 24 days in one small lifeboat. After three days their food supply ran out.

It looked bad for Rickenbacker and his friends. On the 8th day, a seagull inexplicably settled on Eddie’s head. That bird became dinner (raw) for the men. The entrails became their fishing bait. The fish they caught sustained the crew until they were rescued on Nov. 13th. They were located more than 500 miles beyond their destination.

All the men suffered from exposure, dehydration and starvation. Rickenbacker, the oldest member of the crew, lost 65 pounds. After a few days rest Rickenbacker continued on, to complete his original mission, and submitted his report to Secretary Simson on Dec. 19th.

After World War II Rickenbacker stepped up his arch-conservative message to the American people, warning of the dangers of a “socialized welfare state.”

The money he received from his speeches he divided among eight “uplift” organizations, such as the Boys’ Clubs, Big Brothers, and the Boy Scouts of America.

As Rickenbacker settled into old age he became increasingly concerned as to the direction America---and the world, were taking, particularly the Communist-inspired race war in Asia and Africa. Even Adelaide, his wife of more than 50 years, and his sons, David and William could not console him. Captain Eddie, an American hero, died in 1973, a discouraged old soldier, still fighting his country’s battles, but engaged in a battle he was not sure we would win.

Source: www.lib.auburn.edu, www.acepilots.com